Financial Times editor and columnist Pilita Clark has a piece that puts REST against the workaholic pose of the current government:

Brexit, one of the most important events in British postwar history, may have been placed in the hands of men and women who have gone without a summer break and worked for days on end for the best part of two months straight.

This is not brilliant. This is loopy.

There is plenty of evidence showing people who work mad hours are more prone to get ill, drink heavily and make rubbish decisions….

A lot of people think they can get by with just five or six hours of sleep a night with no serious dip in performance. Experts say they are deluded: all but a tiny portion of us need a good seven to nine hours a night.

Worst of all, more hours do not necessarily mean more productivity. A study of workers at a global consultancy firm a few years ago found their bosses could not tell the difference between those who toiled for 80 hours a week and those who simply pretended to. [Ed: This is the great study by Erin Reid.]

This is especially striking to me because Boris Johnson (whose penchant for overwork, or at for least crisis-provoking procrastination, I’ve noted here before) is a huge fan of Winston Churchill, and so must be aware that during the war Churchill worked a lot, but also was very disciplined about getting rest when he needed.

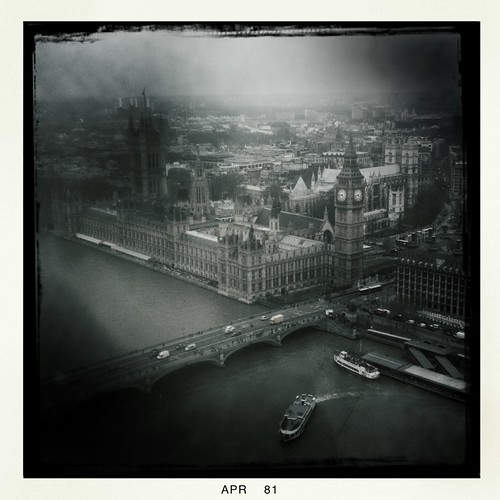

This was driven home to me when I visited the Churchill War Rooms, the underground complex from which he ran the war. Among the meeting rooms, radio rooms, etc., there’s this:

Churchill had a bed installed in the War Rooms, and every afternoon he took a nap. As I explain in REST, Churchill

regarded his midday naps as essential for maintaining his mental balance, renewing his energy, and reviving his spirits. He had gotten into the habit of napping during World War I, when he was First Lord of the Admiralty, and even during the Blitz Churchill would retire to his private room in the War Rooms after lunch, undress, and sleep for an hour or two…. Churchill’s valet, Frank Sawyers, later recalled, “It was one of the inflexible rules of Mr. Churchill’s daily routine that he should not miss this rest.”

A couple other rooms also had small beds in them so his more senior could catch up on sleep when they needed.

Now, Churchill spent a lot of time in the bunker, and it was his command center through the worst of the war, when things looked very dicey for Britain and the Allies. Yet, he still made time for rest. I think it’s hard to argue that this didn’t improve his decision-making and leadership, but it also had a subtler impact, I think:

Not only did a nap help Churchill keep up his energy, his sangfroid also inspired his cabinet and officers. Napping during boring parliamentary debates was one thing. Going to sleep literally while bombs were falling signaled Churchill’s confidence in his staff and his belief that the dark days would pass.

Hitler, in contrast, was famous for his erratic sleep habits and reliance on drugs to keep himself going for long periods. If you wanted someone who illustrates how working long hours doesn’t lead to better results, you couldn’t find a better example. (Indeed, the whole Reich turns out to have been really into stimulants: they described meth as “National Socialism in pill form.”)

And it didn’t send a good message to his subordinates. There’s no better way to say “I don’t trust you to do a good job” than overwork.

One other point: if you read the comments on the piece, they’re basically why I’ve written my next book:

This all sounds good, except if you work for a company that demands that you work 24/7, you will lose your job if you don’t deliver. I worked for several companies, on salary, that gave you so much work to do that you had to work virtually 7 days a week to get it done….

Japanese and Koreans, who unnecessarily hang around the workplace after 5pm, need to read this.

My partner is Japanese and is angry at that part of Japanese work culture. I used to work for a large corp in Tokyo and during our busy season we’d stay until midnight. However, after 5/6 pm every day I’d notice a dramatic drop in my energy and focus.

Lots of comments point to the structural impediments that constrain people from working more effectively, and working less; and they’re absolutely right that there are hard limits to how much we can do as individuals to reduce our working hours. This is why it’s important, I think, to show how to change the structures, to look at the companies (in the UK, Asia, United States, and elsewhere) that are already moving to 4-day or 30-hour weeks, and to learn from them how to redesign work.

Also, if the FT firewall gets in your way, there’s also this reprint in Channel News Asia.