UK-based futurists Andrew Curry, Victoria Ward and Sabine Jaccaud have recently completed a study of the future of the library. Ward’s company Spark Now has a description of the project on its blog, and this jumped out at me:

The future of the library is, in some way, a paradox. So many of the long term trends are running against it that it is easy to assume that it is an anachronism of the 19th and 20th centuries. It is worth spelling this out. Such trends include the rise of digital technologies, and the accompanying rise of audio-visual culture; the long wave of individualism since the late 1960s; the shift from public provision to personal provision; the pressures on public expenditure; the emergence of the e-book and the digitization of books generally. It seems only a matter of time before the library withers away.

But look again, and some other, emerging, trends come into focus. Rising oil prices and greater work flexibility increase the value of the local; the rise of digital rights management fuels campaigns around openness; the number of books published every year continues to rise; issues of access and equity – and affordability – come into sharper focus as one austere year rolls into another; the relationship between the tangible and the digital object becomes increasingly complex; new attitudes to ownership (using, not having) make the library appear as a pioneer.

Look again, and you can start to think that if libraries did not exist, it would be necessary to invent them. But what sort of library would we invent?

They go on to describe a variety of functions that libraries past and present serve, and While it’s a nice piece– any defense of libraries that tries to take them seriously, and not just defend them on the grounds that they’re Timeless Monuments of Civilization or whatever– like lots of discussion of libraries, I think it leaves out something important that most of us overlook, but which I’ve become convinced is very important.

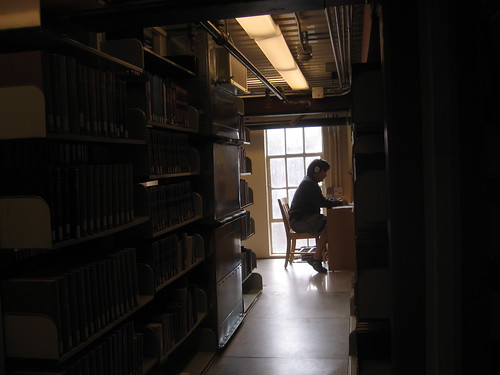

The best libraries are public spaces that support focus and contemplation.

uc berkeley, via library set on flickr

It’s easy make the argument that all these elements– the public, the space, and the contemplation– are anachronistic, or can be more efficiently supported elsewhere, or need to be combined in different ways– and there are times when that might be appropriate. But predictions that the computer would lead us to a paperless office and future fell afoul of the affordances of paper and the role that those affordances play in supporting forms of work as different as corporate brainstorming, air traffic control, and treating hospital patients, and the wrong kind of library is no more likely to succeed in a more-digital future than a library without books would have survived in the past. (The concept of “affordances” comes from Harper and Sellen’s Myth of the Paperless Office, and is one I’ve discussed elsewhere and used in my own work.)

uc berkeley, via library set on flickr

One of the things plenty of people argue now is that the library is a community or collaborative space. Forget the idea of the library as a place where people sit quietly, and frumpy women in sensible shoes go “shhh.” Today’s libraries are incubators, collaboratories, the modern equivalent of the 17th-century coffeehouse: part information market, part knowledge warehouse, with some workshop thrown in for good measure.

seattle public library, via library set on flickr

But libraries need to be recognized as institutions that have also supported another incredibly important, and very hard, kind of creative work: the work of the solitary reader, the person who has to lock themselves away with books and ideas in order to produce something worth sharing with others, to have ideas that are worth trading in the scholarly bourse. Of course it’s important to have spaces that support serendipitous hallway conversations, shop talk, and creative brainstorming; but where do those ideas come from in the first place? The tacit assumption tends to be 1) they arise in those spaces, or 2) Starbucks or people’s offices– in other words, spaces that libraries don’t really have to worry about any longer.

new york public library, via library set on flickr

But for many people, or for people at certain stages in their work, there’s nothing quite like libraries for supporting deep, contemplative work. For one thing, libraries have Lots of Books. This is a fact that we tend to overlook, but even my local public library (which is pretty good, but not huge) has several orders of magnitude more books than I could ever hope to own. And yes, while it’s now possible to have thousands of books in a Kindle, reading scholarly work on a Kindle is awfully hard, because scholarly reading is a martial art.

There’s another element of this publicness that makes libraries work. The example of others working can energize a space and the people in it. In a place like a library reading room, working scholars become public characters, figures who define the quality of a space, set its tone, enforce its formal rules and cultural norms, and serve as examples for each other. Of course, it’s possible for people to be distracting and annoying, just as someone who talks in a movie theatre or forgets to turn off their cellphone during a concert can be annoying; but when it works, that sense of solidarity can be a great thing.

stanford library stacks, via library set on flickr

I think we underestimate the value of public contemplation, and particularly in an era a lot of public discourse around libraries talks about them being community resources or trading zones, it’s necessary to remind ourselves how good libraries can still be havens for thoughtful engagement with ideas.

It’s also worth noting that this function remains an important one in good new libraries. For example, consider this description in the Guardian of the new Canada Water library in Southwark, which explains why it looks like an inverted pyramid:

The best form for a reading room is wide and horizontal, but there was not enough space for this at ground level, squeezed between the tube exit and the waterside. So the reading room is at the top, with the building widening as it ascends to make space for it, with the added benefit that the most important part of the building is placed high up – if not in the clouds, at least sufficiently far from the ground to feel removed and a little dreamy, as a library should.

Raised, it makes occasion for the spiral staircase, which in turn makes the business of going somewhere for a book into a little event or ceremony, rather than a sideways drift such as you might make into a supermarket.

It’s a space I look forward to visiting in my next trip to London.