Mark Riva, one of my semi-regular Twitter correspondents (followers isn’t quite the right word, nor is friend), raises a good question about the term digital detox:

Unfortunately, for some people the term seems to be the right one: for them, a period offline feels necessary to break bad habits or addictions, for which “detoxing” is a familiar response.

In other cases, though, “detox” is simply an easy word to use: it’s familiar, lots of other people use it (there’s a digital detox vacations company now), everyone more or less knows what it means, and it has a bit of a medical/healthy ring that suggests a certain amount of virtuous suffering. But Mark is quite right: the term detox does suggest a level of toxicity and unnaturalness, and it’s not clear that that’s a useful way to think about the downsides of our high-tech lives. It suggests a natural opposition between ourselves and our devices: that living with always-on tools is a bit like working in an factory that exposes you to lots of pollutants.

In this model, you need a regular break to get them out of your system. (Though even on vacation, we may choose to allow in the occasional screen.)

But I think that for many of us, the metaphor of the detox isn’t that useful: at their best, digital devices aren’t pollutants, but extensions of ourselves. This is why I think the term “digital Sabbath” is better than digital detox. Specifically:

It’s cyclical. The Sabbath comes around every week. The fact that it’s a constant feature of life makes it easier to observe; as Jennifer Bleyer put it, it’s like going to the gym– it seems like a pain before, but when you do it it feels great. If you’re glued to screens– or more precisely, if your everyday is one that promotes an unhealthy or addictive relationship with your devices– having a day a week, every week, when you’re free to change that relationship, is very valuable.

It’s sustainable. Unlike a one-time detox or cleanse, it’s not something you only expect to do once… until the next time you do it. Nor is it a complete break from your normal life. One challenge a silent retreat or visit to a monastery presents is that while it’s amazingly restorative, it’s hard to carry its virtues back to your normal life. A weekly practice stands a better chance of improving your life.

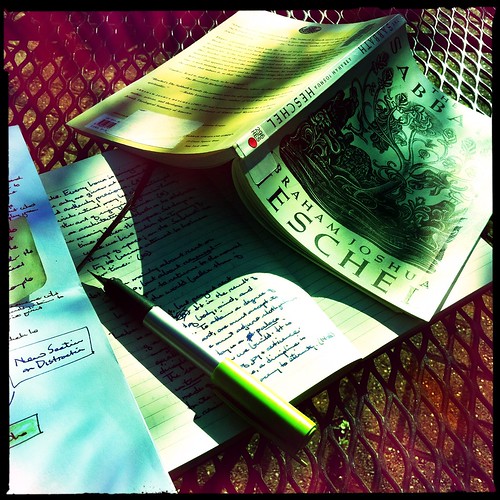

It’s less about getting away from the regular, than reaching for something different. As Heschel wrote, the Sabbath offers an opportunity to “become attuned to holiness in time,” by building a “palace in time… made of soul, of joy and rectitude… a reminder of adjacency to eternity.” It’s a day when it’s all right to “collect rather than to dissipate time,” to “mend our scattered lives.” Heschel’s Sabbath is a counterbalance against modern “technical civilization,” a way “to work with things of space but to be in love with eternity.” To put it another way, it not simply a day-long penalty box in which you’re going to twitch nervously and miss your beloved iPhone; done properly, it’s a chance to experience a very different kind of time, and a different kind of life.

The term “Sabbath” turns some people off because of its religious overtones, but I think that’s a feature, not a bug: it lets you appropriate (in an Alain de Botton, Religion for Atheists kind of way, if that’s your thing) a huge body of knowledge about Sabbath practices, and the virtues of having a day a week that’s set apart from normal life. Abraham Heschel’s short, marvelous book The Sabbath was first published in 1951, but it’s just as relevant today (I talk about it at length in an earlier post); the Jesuits know plenty about the value of contemplative practice and retreats (as do the Benedictines); so does Quaker theologian Richard Foster; and the list could go on and on.