The first big talk I gave about contemplative computing was at a conference on technology whose theme was “Slow.” Last night I revisited that ground: I spoke at an event sponsored by the Hayden Group, an branding and marketing consultancy. (Do we say consultancy in America?) They run a great speaker series, and my friend Rich Green and I talked about slow technology in its various manifestations.

rich showing off slow technologies, via flickr

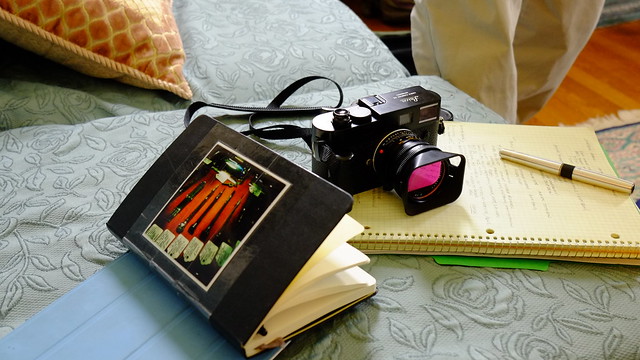

Rich showed a number of slow technologies, including some very old cameras, computing devices (slide rules and the like), and notebooks.

old and new cameras (Zeiss Ikon folding camera and iPhone), via flickr

I did a brief overview of the book, as I am wont to do these days. The crowd at these events is very high-powered, with some really smart people who aren’t afraid to express their opinions; but it was that kind of conversation where even the disagreements yielded interesting things.

A couple people raised objections about the artifacts Rich had brought, and whether they would have been considered “slow” in their own time. A camera is a lot faster than a painting, a slide rule is faster than calculating with pencil and paper; even a bow and arrow (which if you read Eugen Herrigel, you associate with Zen and leaves falling from trees and practiced effortlessness) was faster than a club.

zen and the art of archery, via flickr

If that’s the case, then isn’t “slowness” just a kind of nostalgia, a projection of a desire for a once-simpler life (which probably didn’t seem simpler back then)?

We went back and forth on this a bit, and I came to this question: is “slow” a technical descriptor, or is it something else? Put another way, does a “slow” technology have to be one that actually is s… l… o… w… as measured by a stopwatch?

slow, via flickr

Of course, there are no slow technology police, so you can define it however you want. But it seems to me that people who talk about it emphasize or seek a few things.

They want technologies that promote a measure of reflection, even if they’re easy to use.

They offer opportunities for cultivating and using skills. (The disappearance of older skills, and the perspective they encouraged, is what architects complain about when they lament the impact of CAD on architectural education and practice.)

They offer their own inherent pleasures, even as you’re able to use them without regard for their craftsmanship. Like the goblet, you can appreciate its fine details, but you can also ignore it while you’re focused on its contents. Good cameras are a great example of this kind of balance between geeky beauty and utility: the Leica M9 is truly a thing of beauty, but you can also shift your attention away from its heavy precision and use it to see the world.

slow technologies, via flickr

They invite deliberation. As the Slow Media Manifesto declares, “Slow Media are… about choosing the ingredients mindfully and preparing them in a concentrated manner.”

Using them can be so engaging that you lose track of time. This is the other critical form of slowness: not just that you’re doing things at a slower pace than you are in your normal hurried life, but that your sense of time slows and stretches.

foggy park this morning, via flickr

To me, all this points to a conclusion: that the “slowness” is a psychological thing, not a purely technical one. It’s the kind of slowness that comes when you’re so engaged in something you don’t notice the time passing: you look up and four hours have passed, and it’s surprising and blissful.

The exercise of skill that challenges (but doesn’t overwhelm), immersion of attention, time slowing… We’ve all seen this before. It’s Mihaly Csikszentmihaly’s definition of flow. As you’re recall, flow, or optimal experiences involves

a sense that one’s skills are adequate to cope with the challenges at hand, in a goal-directed, rule-bound action system that provides clear clues as to how well one is performing. Concentration is so intense that there is no attention left over to think about anything irrelevant, or to worry about problems. Self-conciousness disappears, and the sense of time becomes distorted. An activity that produces such experiences is so gratifying that people are willing to do it for its own sake, with little concern for what they will get out of it, even when it is difficult, or dangerous. (71)

This psychological dimension, I should add, isn’t one that proponents of slow technology (or other slow experiences) ignore: Jack Cheng describes the Slow Web, for example, as

a feeling we get when we consume certain web-enabled things, be it products or content…. [my emphasis] It’s not so much a checklist as a feeling, one of being at greater ease with the web-enabled products and services in our lives.

But the point is this: looking for slowness in the technologies themselves, or evaluating slow technologies on the basis of whether they’re “really” slow or not compared to today’s technologies or their contemporary competitors, misses the point. The slowness is experiential, and it’s the simplest expression of a bigger set of phenomena that emerge when you’re able to engage mindfully and skillfully with technologies. It’s psychological, a product of your active use of a technology, not something the technology lets your consume.

It took a while to figure this out, and the discussion went about an hour longer than I expected. But I didn’t notice. The time just flew by.