Journalist and “wrongologist” Kathryn Schulz has a long piece in New York magazine about her relationship with Twitter:

I’ve never before gone mad for any type of technology. Even the Internet did not particularly seduce me before the Twitter portal. I used it only for e-mail, and for targeted research; as recently as 2009, I probably spent, on average, under 30 minutes a day online. I didn’t have a cell phone until 2004, didn’t have a smartphone until 2010. I only got addicted to coffee three years ago. But then along came that goddamned bluebird, which seems to have been built with uncanny precision to hijack my kind of mind….

It’s one of the most thoughtful pieces about the upsides and downsides of Twitter I’ve read.

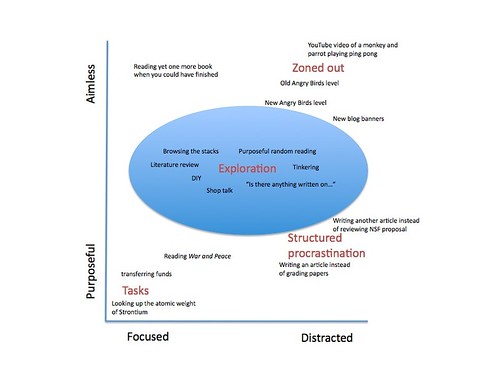

Part of what makes it attractive is not that it’s simply a distraction; rather, “it’s sufficiently smart and interesting that spending massive amounts of time on it is totally possible and semi-defensible.” It occupies a space somewhere in the “exploration” space of the graphic I described a couple years ago.

The particular strength of the piece is that, as well as anything I’ve seen, it explains why Twitter is especially appealing to writers– and why that appeal is a two-edged thing:

A tweet is basically a genre in which you try to say an informative thing in an interesting way while abiding by its constraint (those famous 140 characters) and making use of its curious argot (@, RT, MT, HT). For people who love that kind of challenge — and it’s easy to see why writers might be overrepresented among them — Twitter has the same allure as gaming. It is, essentially, Sentences With Friends.

It’s a bit like speed chess as described in Waiting for Bobby Fisher. At one point the chess master (Ben Kingsley) explains to his young student that speed chess is fun, but destroys your ability to play serious games.

I am convinced that steadily attending to an idea is the core of intellectual labor, and that steadily attending to people is the core of kindness. And I gravely worry that Twitter undermines that capacity for sustained attention. I know it has undermined my own: I’ve watched my distractibility increase over the last few years, felt my time get divided into ever skinnier and less productive chunks.

More disturbing, I have felt my mind get divided into tweet-size chunks as well. It’s one thing to spend a lot of time on Twitter; it’s another thing, when I’m not on it, to catch myself thinking of — and thinking in — tweets. This is a classic sign of addiction: “Do you find yourself thinking about when you’ll have your next drink?” etc. In context, though, it’s more complicated than that, because thinking in tweets is only a half-step removed from what I’ve done all my life, which is to try to match words to thoughts and experiences. The job of a writer is to do that in a sustained way — a job I find brutally hard, and, when it works, deeply gratifying. The trouble with Twitter is that it produces a watered-down version of that gratification, at a very rapid rate, with minimal investment — and, if I am going to be honest with myself, minimal payoff, and minimal point.

It’s not just that training your brain to write in 140 characters can wither your ability to concentrate in the kind of serious, sustained way every writer finds is essential to write books; the very public, immediately rewarding nature of the writing is also a problem. Schulz talks about spending years in a virtual cave when she was writing her book. “In my experience, and the experience of most writers I know, that cave is the necessary setting for serious writing,” she says. “Unfortunately, it is also a dreadful place: cold, dark, desperately lonely.” (I agree completely that it’s essential for every writer, but I find it a more felicitous place; still, I get what she means.)

Twitter, by contrast, is a warm, cheerful, readily accessible, 24-hour-a-day antidote to isolation. And that is exactly the issue. The trouble with Twitter isn’t that it’s full of inanity and self-promoting jerks. The trouble is that it’s a solution to a problem that shouldn’t be solved. Eighty percent of the battle of writing involves keeping yourself in that cave: waiting out the loneliness and opacity and emptiness and frustration and bad sentences and dead ends and despair until the damn thing resolves into words. That kind of patience, a steady turning away from everything but the mind and the topic at hand, can only be accomplished by cultivating the habit of attention and a tolerance for solitude.

By removing the need to isolate yourself to write, offering an alternative that’s social, and providing immediate emotional rewards (but no financial ones), Schulz is arguing, Twitter lets writers practice a version of their craft that is fun, that is occasionally valuable enough to keep doing (there’s our old friend Mr. Intermittent Rewards!)– but which can also make it harder for writers to do more serious writing.

Not that she has any plan of giving it up (any more than I do). The challenge is to learn to use it thoughtfully, to observe how your usage can unintentionally affect you, and to retake control over it when it tries to push you in a different direction.