Evgeny Morozov has a short critical piece in The New Republic about digital detoxes, mindfulness and technology. I think the swipe at mindfulness is on the shallow side, but his argument that the digital detox movement is problematic– or rather, that it runs the risk of solving one problem by directing our attention away from a bigger problem– is worth engaging.

Morozov sees two problems with the movement. First, digital detoxes aim to help people recharge their mental batteries so they'll have more energy to spend on social media– in effect, it encourages people to live more interesting lives so they won't bore their friends on Facebook, not to rethink how they live.

Second, and more important, the movement makes the individual responsible for overconnection, and implicitly absolves companies of trying to commoditize and resell their user's attention.

In this formulation, the problem with digital distraction is that you spend too much time on it, you allow yourself to be distracted– not that Facebook and Twitter and Netflix spend enormous amounts of money and energy testing design tweaks to get you to spend more time on their services, so they have more of your attention and information about you. As Morozov says:

our debate about distraction has hinged on the assumption that the feelings of anxiety and personal insecurity that we experience when interacting with social media are the natural price we pay for living in what some technology pundits call “the attention economy.”

But what if this economy is not as autonomous and self-regulating as we are lead [sic] to believe? Twitter, for instance, nudges us to check how many people have interacted with our tweets. That nagging temptation to trace the destiny of our every tweet, in perpetuity and with the most comprehensive analytics, is anything but self-evident….

In reality, he concludes, "With social media—much like with gambling machines or fast food—our addiction is manufactured, not natural."

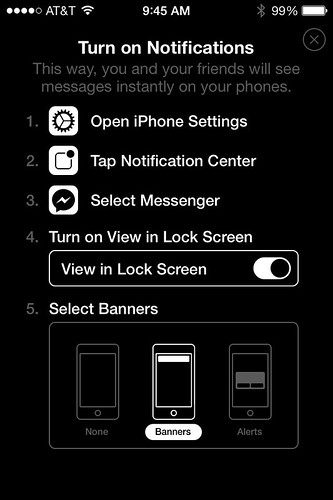

If this seems a little abstract, let me give an example. Recently I loaded Facebook Messenger, a stand-alone app that gives you access to Facebook's instant messaging service, onto my iPhone. Every time I open the app, I get this screen:

Messenger really really wants me and my friends to "see messages instantly on your phones." Why? Because they know that many users look at Messenger more often if we have notifications turned on (if only to stop the damn thing from ringing), and that this is their best shot at competing with ordinary SMS. It's not a very subtle nudge.

You might argue that this kind of thing is harmless, and besides that technologies are neutral. But both those arguments are wrong. Built into Messenger's "Turn on Notifications" screen is an assumption that instantaneous communication is always best; that you should always be willing to direct your attention to messages and Messenger; and that when talking to people, speed trumps things like deliberation or thoughtfulness. It reflects the desires of its makers to commoditize our attention, to gather information about where we are and what we're doing, both to do ostensibly good things (improve the service) and not so great things (sharpen locative advertising).

This is a perfect little example of what users face today: a near-constant exposure to efforts to shape their behavior in ways that might serve them (at some times), but definitely serve the interests of companies and advertisers.

Ironically, critics who see the digital detox movement as one that fetishizes analog authenticity enable this (or as it were, distract us from the real issue):

in their efforts to reveal the upper-class biases of the "digital detox" crowd—by arguing, for example, that the act of unplugging falls somewhere between wearing vintage clothes and consuming artisanal cheese—critics like [Alexis] Madrigal risk absolving the very exploitative strategies of Twitter and Facebook.

I think Morozov is exactly right that there's a danger that practices like a digital detox or digital Sabbath can be shallow, and that we can miss the opportunity they offer us to rethink how we use our information technologies. But any good thing can be practiced in a shallow way (this is why we have the words humility and sanctimony), and any good opportunity can be wasted.

But it's not inevitable that they're shallow. It's important to note that there are people for whom digital detoxes actually work the way Morozov advocates. When I wrote The Distraction Addiction, I made a point to talk about people for whom disconnection isn't a fad or a quick fix. The people who get the most out of it are the people who practice it regularly. They often discover that they don't need to be frantically connected, and they become a little more aware of how companies try to capture their attention. And they realize that the challenge isn't to disconnect completely or get back to "real life," but to lead a richer life. They're still going IRL, but going for a different "R."

It's easy to treat digital detoxes as a one-time solution, or to apply the vitamin theory of interaction to them. We often talk about technologies as having a clear, linear impact on us (e.g, more video games = BAD), but they don't work on us that way. Likewise, detoxes and sabbaths don't operate (or fail) in straightforward ways.

I understand why Morozov wants us to be aware of how companies try to capture and commodify our attention, and I think it's a valuable thing; but I'm skeptical that social media companies will change their strategy. The idea that users are lizard-brained consumers who can be nudged to play or watch or like a little longer is just too appealing. This is why I aimed my book at ordinary users: I can't change Facebook or Google, but I can help people change themselves. The challenge is to encourage users without excusing the strategy.