[This is the second of several posts drawing on my the talk I gave at the NAIS annual conference. The first is here.]

How are technologies designed to distract students (and their parents and teachers)?

Some people talk about how the shiny-blinky flashing Internet appeals to our visually-oriented brains, how Facebook likes and retweets give us a little shot of dopamine. But these effects aren't merely an accident. Technology companies actively design to maximize our engagement with them. (It's the downside of the desire to create technologies that are compelling and user-friendly. It's easiest to ignore technologies that are clearly broken.) Here I'll give a couple examples of how these designs work.

In their fabulous book Nudge, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein explore the power of default settings, and explain how they can be used for good or evil. Retirement plans that automatically maximize employee contributions, and increase as salaries go up, yield richer nest eggs than those that have to be actively managed. (Everyone means to manage their retirement portfolios or put more away for their old age, but today's credit card statement always calls louder than your need for money thirty years from now.) You can get kids to eat healthier school lunches by making the fruit more accessible than the cake: kids who default to having whatever's easiest at hand will opt for the apple instead of the apple pie. (I write more about Nudge and its ideas here, here, and here.)

this is a nudge; you can download the iPhone-optimized version

In the technology sphere, defaults can have just as powerful an effect on behavior, and designers have quickly learned how to set defaults to keep users watching longer, sharing more, or interacting for longer periods.

For example, Netflix, which helped popularize the concept of binge watching, has a brilliantly evil design element. When you’re watching a TV series, at the end of an episode Netflix automatically queues the next show. The default is to keep watching.

Now given that plenty of people binge-watch it's not an obviously unreasonable design choice; but it does make it much easier to rationalize one more episode of Breaking Bad when you should be turning out the light.

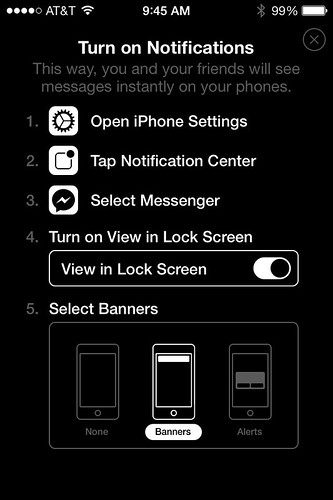

The iPhone app Facebook Messenger offers another example of how defaults ensnare our attention. When you open the app, the first thing you see if not a list of your friends or recent messages; you see step-by-step instructions to make sure that “you and your friends will see messages instantly on your phones.”

If you don't change those settings, you'll see the instructions again the next time you open the app, and the time after that, and the time after that. Messenger, and Facebook, really want you to make this your default. The more you interact with it, the more it learns about you—where you are, when you’re messaging, who you’re messaging with.

Finally, there are cases where designers harness social obligation to keep you using their service. Web services that offer you the chance to invite your friends to join are banking on the theory that The game Drawsome, for example, is an open-ended game in which players guess what their friends have drawn.

But you don't just play with friends; the game uses social obligation to keep you playing.

For one thing, it's a cooperative game: you only get points if I correctly guess what you've drawn. Second, it's open-ended: the instant I correctly guess your drawing, the game starts the next round. There's no graceful exit, no way to agree in advance (within the game, anyway) to stop after a certain number of rounds. Quitting the game means quitting on your friends.

The examples of Netflix and Facebook Messenger and Drawsome could be multiplied endlessly, but they illustrate how social media, gaming, and entertainment companies now spend enormous amounts of time and energy trying to get you to spend more time interacting with them, to recruit your friends to join them, and to intentionally or accidentally share as much information as possible with them.

Perhaps it's no surprise, given the degree to which designers trigger social responses, that we've come to treat our smartphones like children.

how smartphones behave like kids, via youtube

In addition to the powerful commercial imperative behind these designs, there’s also a deeper assumption at work: that for all kinds of reasons, connectivity ought to be the default in our lives. That we should always be accessible to the world, always broadcasting our status to friends, and "sharing" our location with media companies and advertisers. We have the ability to be always-on, therefore we should be.

This can have negative consequences for adults: it leads to a sense within workplaces that you should never be inaccessible to bosses or clients, that you're obliged to respond instantly no matter how urgent or trivial the subject.

But for kids who are figuring out themselves and their place in the world, this kind of hyperconnection may have a significant developmental impact. Parents and teachers need to learn how to can help kids become more mindful about how they use information technology, how they interact with others through it, and what place they allow it to have in their lives.

As Catherine Steiner-Adair put it, we need to help our kids become smarter than their smartphones.

I'd say we need to help them learn to use them skillfully enough to take full advantage of the technologies, and to see that mastering these technologies can make them become smarter, better, and even more resilient and compassionate people.

And by "we," I don't just mean some generic "someone in society:" I mean schools.