I’ve been thinking about different forms of distraction, and the differences between distraction and mind-wandering. We talk a lot about focus and distraction, and often talk about them as if they’re two different mental categories. Like many everyday terms, we don’t use formal definitions; we just take for granted that they’re different, and that one (focus) is good, and the other (distraction) is bad.

When we talk about distraction, we can be talking about a multitude of things. For example:

- Texting while driving;

- Texting during dinner;

- Spacing out (e.g., staring out the classroom window, wool-gathering);

- Playing video games when you should be doing homework;

- Focusing on the wrong thing (e.g., a CEO who micromanages his office redecoration while the company tanks);

- Not being able to read War and Peace because your attention has been eroded by email and cat videos.

Likewise, we tend to use distraction and mind-wandering somewhat interchangeably, or at least recognize that there’s some overlap between them. Some examples of distraction definitely involve mind-wandering: staring out the window rather than paying attention to the teacher, for example, is an example we’re all familiar with.

But if we’re to make the argument that mind-wandering is beneficial, I think it would be useful to explain how despite our common usage, mind-wandering is actually quite different from distraction— and indeed, that distraction is a little more multifaceted that we usually think. It’s always worth knowing your enemy.

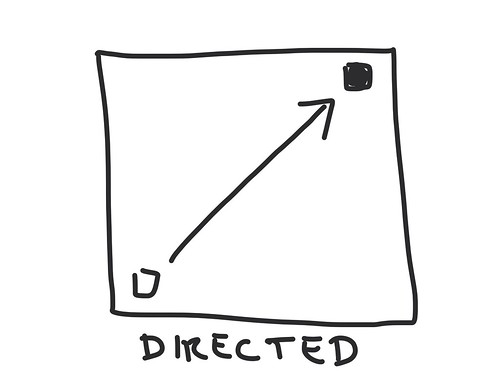

First, let me explain the critical components of focus, or what I’ll call Directed Attention. Consider the crude drawing below.

This is directed attention. You have something that you should be focusing on (the square in the upper right), and you direct your attention at it. There are two important components to this scenario:

- You’re focused on something;

- Your focus is under your control;

- You’re focused on the right thing at the right time.

So if you’re driving, this would be you watching the road, the traffic, etc. If you’re reading, you’re paying attention to the words, not just scanning the page while you think about something else.

Now, what happens when you’re distracted? Distraction isn’t a single condition; I can think of two major kinds of distraction.

Let’s call the first Hijacked. It looks like this:

In this case, you ought to be paying attention to the square in the upper right— and for a while you were— but then your attention is captured by the shiny blinky thing on the left, and you veer off-course and pay attention to that instead.

- You’re focused on something;

- You’re not in control of your attention;

- You’re focused on the wrong thing.

For example, if you’re driving, you take your eyes off the road because your phone tells you that someone’s liked your last tweet. Or you’re reading War and Peace, and you get a notification that something is happening on the Internet.

I use the term hijacked because the shiny blinky thing may be designed to capture your attention, or behave in ways that assume that you should pay attention to it whenever it wants you to. In other words, this is not accidental.

My favorite example of a technology designed this way is the Facebook Messenger iPhone app, which is constantly reminding me that I haven’t turned on notifications, and that I really, really should. It (or rather Facebook Messenger’s designers) assumes that my attention should be interruptible whenever it decides, and that failing to do constitutes an error on my part. (I haven’t figured out how to switch this off, and consequently rarely use Messenger on the iPhone. But since research has revealed that even awareness of notifications is distracting, I’m standing my ground.)

The other important thing about having your attention hijacked is that you’re still paying attention to something: your attention is diverted, pulled away, but it’s not diffused. You may be focused as intently on the shiny blinky thing as on the thing you should be concentrating on. Any parent who’s had to pull kids away from a video game or the television when they should be getting ready for dinner or doing their homework understands the power of this kind of distraction. it’s not that the kid is failing to focus; it’s that they’re focused on the wrong thing at the wrong time.

So this kind of distraction isn’t about not being able to concentrate; it’s about concentrating on the wrong thing at the wrong time, and doing so because your attention is pulled away. It’s the state of “machine flow” that makes Vegas casinos rich. It’s the conscious effort to capture and commoditize your attention that critics of social media and videogame design protest against.

Note that a “distracting” social media service or video game isn’t interested in you never being able to pay attention to anything; it just wants you to always pay attention to it. It wants to be the shiny-blinky thing that you pay attention to, instead of whatever else you’re doing. The objective isn’t to put you in a state of constant partial attention, but to hijack and hold your attention for as long as possible.

There’s another kind of distraction, which I call Aimless. It looks like this:

In this case, you should be directing your attention at the object in the top right, but instead your attention just goes around randomly. This is what Buddhists call the monkey mind, the mind that never pays attention to any one thing for very long, and indeed cannot focus on anything. In this case:

- You’re unfocused;

- You’re not in control;

- You’re focused on the wrong thing (or nothing).

For example, you’re in the car and you should be paying attention to traffic, but instead your attention drifts in quick sequence to a dozen other things. Or you should be reading War and Peace, but instead you’re mindlessly clicking through Buzzed listicles of the best Buzzed listicles.

Now, so far as I can tell, nobody tries to promote aimlessness: Facebook and Twitter and Netflix and EA don’t gain anything by having you not be able to pay attention to them for any length of time. Aimlessness is a product of cognitive overload, of having too many different things competing for your attention and weighing on your mind. This is the state that Nicholas Carr complains about in The Shallows.

Of course, you can move between these forms of distraction. Consider the following schedule:

- Minutes 1 to 7: Read War and Peace.

- Minutes 8 to 19: Your attention is hijacked by a push notification telling you that three people have liked / retweeted your last tweet. Scroll through your timeline.

- Minutes 20 to 131: A retweet of a funny Onion article leads you to click aimlessly between listicles about bad prom photos, the year’s cutest kittens, and the best legislative debates that turned into brawls, a video of dogs quipped with GoPro cameras, two videos of animals attacking GoPro cameras, and two Daily Show monologues.

- Minutes 132 to 134: Try to finish reading War and Peace before having to go teach War and Peace in class.

One other essential thing to notice about distraction is that it’s not just a measurable cognitive state: it’s a contextual thing as well. Distraction requires being distracted away from something, whether it’s an object you should be looking at, a piece of music you should be listening to, a task you should be completing.

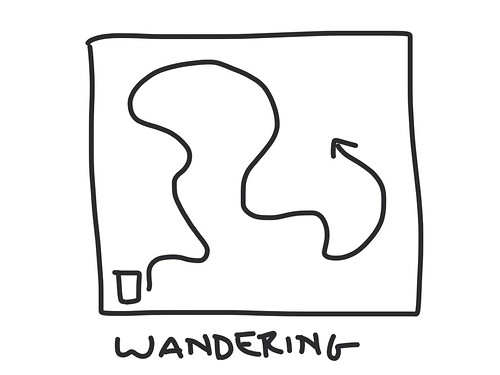

So how does mind-wandering differ from these forms of distraction? This to me is what Wandering looks like:

In this instance, your attention isn’t focused on any particular thing, but it doesn’t need to be; you can safely let your thoughts go off on their own and spontaneously generate, because you don’t have something you need to concentrate on. In other words:

- You’re unfocused;

- You’re not in control— but, and this is important, neither is anyone else;

- You’re not supposed to be focused on something.

For example, if you’re doing something completely automatic, like folding laundry or unloading the dishwasher, you can pretty safely let your mind wander.

To continue the geographical metaphor, I quite enjoy walking around places like London and Cambridge because I can just wander around them, with no set destination, nowhere I need to be, but a pretty good likelihood that I’ll come across something interesting.

It’s this absence of a goal, the absence of pressure to focus on something, and the fact that no one else (or nothing else) is trying to hijack your attention, that distinguishes wandering from distraction. Wandering and distraction aren’t distinctive brain states that you could identify in an fMRI; they differ because of a mix of intention, control, and context.

But psychologically, there’s a very big difference between letting your mind drift while you’re walking the dogs or lingering over a cup of coffee; having a long to-do list but not being able to focus on any specific thing because your brain refuses to focus; having a long to-do list but not doing any of it because something shiny and blinky is capturing your attention.